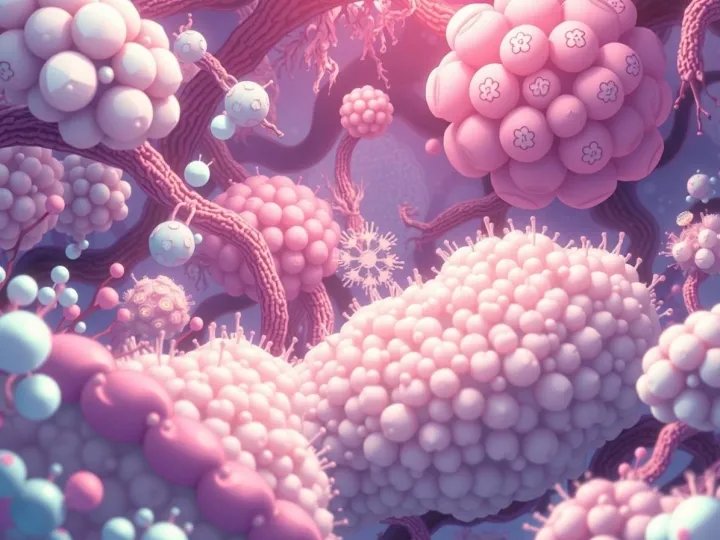

The idea that food fuels the body is ancient. But food that shapes thought? That belongs to the frontier of psychobiotics. A growing body of research suggests that probiotics - living microbes we once valued mainly for digestion - may also influence memory, decision-making, and emotional balance through the gut - brain axis.

A recent study developing probiotic-coated biscuits and dates in Egypt shows how simple, locally rooted foods can carry stabilized strains of beneficial bacteria . On the surface, this is food technology: edible films made from whey protein and alginate kept Lacticaseibacillus and Lactiplantibacillus strains alive through storage and digestion. But the deeper implications emerge when we connect this work to the psychobiotic field.

Psychobiotics are microbes with measurable effects on the mind. As Ehrmann and colleagues note (Microorganisms, 2022), strains used in traditional fermentation - the same families of bacteria now stabilized in biscuits and dates - can act as cognitive modulators. Through neurotransmitters like serotonin and GABA, as well as through immune and hormonal signaling, they influence anxiety, mood, stress reactivity, and even learning.

How the Gut - Brain Axis Works

The gut - brain axis is the communication superhighway linking digestion to cognition. It operates through several overlapping channels:

1. Neurotransmitters.

Many gut microbes can produce or influence brain chemicals such as serotonin, dopamine, and GABA. In fact, most of the body's serotonin is made in the gut. These molecules affect mood, memory, and decision-making when signals travel to the brain.

2. The vagus nerve.

This cranial nerve runs directly between the gut and the brainstem. Microbial activity in the gut can stimulate vagal pathways, sending rapid signals that influence stress responses, appetite, and emotional regulation.

3. Immune signaling.

Gut microbes interact with immune cells lining the intestine, which release cytokines - chemical messengers that influence inflammation. Chronic inflammation is strongly tied to depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline.

4. Metabolites.

Probiotics also generate short-chain fatty acids (like butyrate) that strengthen the gut barrier and support brain function by reducing oxidative stress and modulating gene expression.

Together, these systems make the gut not just a digestive organ, but a cognitive partner. When the microbial community is healthy, signals tend to promote resilience and balance. When disrupted - by stress, antibiotics, or poor diet - the axis can tilt toward anxiety, low mood, or impaired focus. Psychobiotics aim to restore this balance by using targeted microbial strains to "tune" the gut - brain dialogue.

That means the Egyptian team may not just have made longer-lasting probiotics. They may have created a delivery system for cognition-altering microbes. A date enriched with L. rhamnosus could, in theory, one day support emotional resilience. A biscuit with L. plantarum might help regulate stress-induced inflammation that clouds decision-making. The gut is not a passive vessel; it is an active partner in how we think and feel.

What makes this story compelling is its accessibility. Instead of expensive supplements or lab-based interventions, psychobiotics could ride into daily life on the back of ordinary, culturally familiar foods. Functional foods that require no shift in behavior may be the fastest way to weave psychobiotic effects into society. In regions where mental health resources are scarce, such foods could become quiet allies in preventing stress-related disorders.

The message is both scientific and symbolic: cognition is not sealed inside the skull. It is porous, influenced by microbes, meals, and metabolic flows. To "feed the mind" may soon mean more than reading or meditation - it may mean choosing foods designed not only to nourish, but to tune the field of consciousness itself.